Adventure Magazine

Issue #236 Xmas 2022

Issue #236

Xmas 2022

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

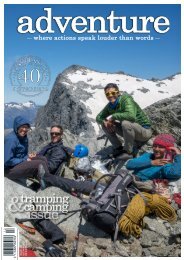

Our bivvy site, under Envers des Aiguille, where constant rockfall disturbed our sleep.

"This is always a disconcerting sight for

a climber. It was especially alarming

because we watched the debris peter

down towards a gully where we’d been

planning to venture in the coming days."

This is always a disconcerting sight for a climber. It was

especially alarming because we watched the debris peter down

towards a gully where we’d been planning to venture in the

coming days. The gully was the access to 375m-long alpine

climb called Sala Athee, on the peak known as The Monk, which

was recommended to us because of its technical crack climbing.

We were sitting in an idyllic bivvy spot below the granite needles

of Envers des Aiguilles, near Chamonix, in the heart of the

European Alps. The rockfall wasn’t anywhere near us, but

witnessing such a large one always focuses the mind on what

might fall down at any moment.

All through the night, the unnerving sound of collapsing rocks

echoed around us. If I happened to be awake, there was little to

do but hide in my sleeping bag and hope we weren’t in the direct

path of anything.

The following day, as we scaled the jagged corners and

technical slabs of a 650m-high climb called Banana Republic,

we remained on constant alert to the possibility of rockfall,

which, thankfully, never eventuated.

We had chosen the climb because it had less objective danger

than other routes in the Mont Blanc massif. The European

summer had been a sweltering affair, and many of the glaciers

in the alps were already opening up. In early July we had

crossed the Valle Blanche to climb the magnificent granite tower,

Grand Capucin, and were later told that a guide and his client

had both fallen into a crevasse, breaking several bones, while

crossing the same glacier at around the same time as we had.

A week before that, a serac the size of two football fields

collapsed from the top of the Marmolada Glacier, in the Italian

Dolomites, killing 10 people. It’s still unclear how it happened,

but it wasn’t an area known to be dangerous, nor was it a

hanging glacier, where icefall would be expected. But rising

temperatures have made glaciers more unstable; leading up to

the accident, a weather station at 3250m on the Marmolada had

recorded 23 straight days of temperatures above 0 0 Celsius.

These are uncertain times, as rising temperatures change

the face of the mountains we love to play in. Over the last

century, temperatures in the European Alps have gone up by

2 degrees Celsius, twice the global average. Climate change

has contributed to glaciers shrinking by more than a third over

the last 18 years. And while scientists expect the Marmolada to

disappear altogether within 15 years, others predict all glaciers

in Europe below 3500m will have gone by 2050.

The same pattern has been observed in New Zealand, which in

general means the snowline is creeping higher while the volume

of ice shrinks. Studies from the National Institute of Water and

Atmospheric Research show that a third of the permanent snow

and ice in the Southern Alps was lost between 1977 and 2014.

More recently, New Zealand glaciers have been shown to have

lost 1.5m a year from 2015 to 2019, almost seven times as much

compared to the thinning that occurred between 2000 and 2004.

As a globe-trotting dirtbag climber for more than a decade, this

poses a dilemma: how to offset the carbon footprint of someone

who regularly undertakes long-haul flights and super-long

drives. Some feel so guilty about their impact on the planet that

they no longer indulge in visits to far-flung climbing destinations.

8//WHERE ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS/#235