Adventure Magazine

Issue #236 Xmas 2022

Issue #236

Xmas 2022

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

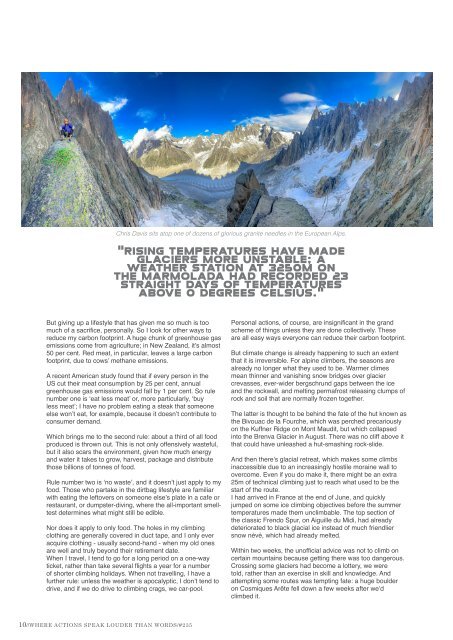

Chris Davis sits atop one of dozens of glorious granite needles in the European Alps.

"rising temperatures have made

glaciers more unstable; a

weather station at 3250m on

the Marmolada had recorded 23

straight days of temperatures

above 0 degrees Celsius."

But giving up a lifestyle that has given me so much is too

much of a sacrifice, personally. So I look for other ways to

reduce my carbon footprint. A huge chunk of greenhouse gas

emissions come from agriculture; in New Zealand, it’s almost

50 per cent. Red meat, in particular, leaves a large carbon

footprint, due to cows’ methane emissions.

A recent American study found that if every person in the

US cut their meat consumption by 25 per cent, annual

greenhouse gas emissions would fall by 1 per cent. So rule

number one is ‘eat less meat’ or, more particularly, ‘buy

less meat’; I have no problem eating a steak that someone

else won’t eat, for example, because it doesn’t contribute to

consumer demand.

Which brings me to the second rule: about a third of all food

produced is thrown out. This is not only offensively wasteful,

but it also scars the environment, given how much energy

and water it takes to grow, harvest, package and distribute

those billions of tonnes of food.

Rule number two is ‘no waste’, and it doesn’t just apply to my

food. Those who partake in the dirtbag lifestyle are familiar

with eating the leftovers on someone else’s plate in a cafe or

restaurant, or dumpster-diving, where the all-important smelltest

determines what might still be edible.

Nor does it apply to only food. The holes in my climbing

clothing are generally covered in duct tape, and I only ever

acquire clothing - usually second-hand - when my old ones

are well and truly beyond their retirement date.

When I travel, I tend to go for a long period on a one-way

ticket, rather than take several flights a year for a number

of shorter climbing holidays. When not travelling, I have a

further rule: unless the weather is apocalyptic, I don’t tend to

drive, and if we do drive to climbing crags, we car-pool.

Personal actions, of course, are insignificant in the grand

scheme of things unless they are done collectively. These

are all easy ways everyone can reduce their carbon footprint.

But climate change is already happening to such an extent

that it is irreversible. For alpine climbers, the seasons are

already no longer what they used to be. Warmer climes

mean thinner and vanishing snow bridges over glacier

crevasses, ever-wider bergschrund gaps between the ice

and the rockwall, and melting permafrost releasing clumps of

rock and soil that are normally frozen together.

The latter is thought to be behind the fate of the hut known as

the Bivouac de la Fourche, which was perched precariously

on the Kuffner Ridge on Mont Maudit, but which collapsed

into the Brenva Glacier in August. There was no cliff above it

that could have unleashed a hut-smashing rock-slide.

And then there’s glacial retreat, which makes some climbs

inaccessible due to an increasingly hostile moraine wall to

overcome. Even if you do make it, there might be an extra

25m of technical climbing just to reach what used to be the

start of the route.

I had arrived in France at the end of June, and quickly

jumped on some ice climbing objectives before the summer

temperatures made them unclimbable. The top section of

the classic Frendo Spur, on Aiguille du Midi, had already

deteriorated to black glacial ice instead of much friendlier

snow névé, which had already melted.

Within two weeks, the unofficial advice was not to climb on

certain mountains because getting there was too dangerous.

Crossing some glaciers had become a lottery, we were

told, rather than an exercise in skill and knowledge. And

attempting some routes was tempting fate: a huge boulder

on Cosmiques Arête fell down a few weeks after we’d

climbed it.

10//WHERE ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS/#235