Malaria & Neglected Tropical Diseases

Highlighting the commitment from the Kigali declaration and looking at how we can deliver political and financial commitment to eradicate malaria and NTDs and avoid resurgence. This Mediaplanet campaign was distributed with the Guardian newspaper and launched on www.globalcause.co.uk on 16-May 2022

Highlighting the commitment from the Kigali declaration and looking at how we can deliver political and financial commitment to eradicate malaria and NTDs and avoid resurgence.

This Mediaplanet campaign was distributed with the Guardian newspaper and launched on www.globalcause.co.uk on 16-May 2022

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Q2 2022 | A promotional supplement distributed on behalf of Mediaplanet, which takes sole responsibility for its content

Read more at www.globalcause.co.uk

Malaria & Neglected

Tropical Diseases

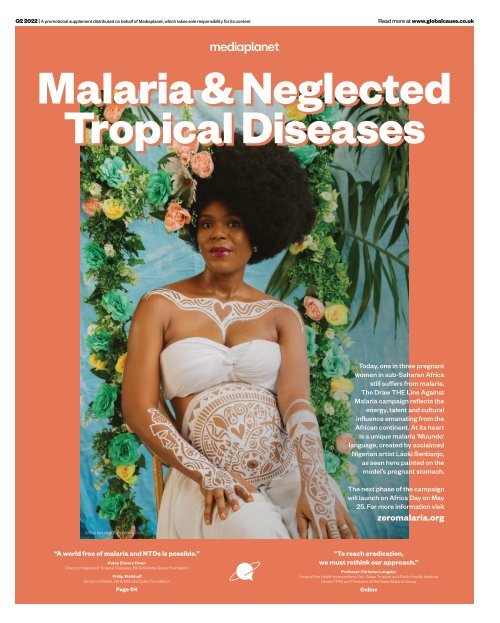

Today, one in three pregnant

women in sub-Saharan Africa

still suffers from malaria.

The Draw THE Line Against

Malaria campaign reflects the

energy, talent and cultural

influence emanating from the

African continent. At its heart

is a unique malaria ‘Muundo’

language, created by acclaimed

Nigerian artist Láolú Senbanjo,

as seen here painted on the

model’s pregnant stomach.

The next phase of the campaign

will launch on Africa Day on May

25. For more information visit

zeromalaria.org

©ZERO MALARIA/ THOMPSON S. EKONG

“A world free of malaria and NTDs is possible.”

Katey Einterz Owen

Director, Neglected Tropical Diseases, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Philip Welkhoff

Director, Malaria, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Page 04

“To reach eradication,

we must rethink our approach.”

Professor Christian Lengeler

Head of the Health Interventions Unit, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute

(Swiss TPH) and President of the Swiss Malaria Group

Online

A PROMOTIONAL SUPPLEMENT DISTRIBUTED ON BEHALF OF MEDIAPLANET, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTENTS

We can end NTDs

but we must show our

commitment now

2022: A pivotal moment

for a more equal world

Incredible progress has been made against neglected tropical diseases (NTDs)

but there is still work to be done. The Kigali Declaration on NTDs, a new political

declaration, provides the opportunity to end NTDs.

NTDs are a group of 20

diseases that affect 1.7

billion people globally; they

can debilitate, disfigure

and kill. These diseases include

elephantiasis, rabies, river blindness

and trachoma. We call these diseases

neglected because they affect the

world’s poorest and they receive less

attention than other diseases.

The effects of NTDs are devastating,

they impair cognitive and physical

development in children. They

lead to school and work absences,

particularly in women and girls

who are often responsible for caring

for their family. They also cost the

economies of endemic countries

billions of dollars and can trap

communities in cycles of poverty.

Recognising the success so far

Over the past decade, incredible

progress has been made against NTDs.

So far, 44 countries have eliminated

at least one NTD and 600 million

people no longer require treatment

for NTDs. Some of these diseases that

have plagued humanity for centuries,

such as leprosy, sleeping sickness and

guinea worm disease are also at an alltime

low. This shows that ending NTDs

is within our power, but there is still

work to be done.

The Kigali Declaration on NTDs

pushes us forward

The Kigali Declaration on NTDs is a

new high-level political declaration

that will launch later in 2022 at the

Kigali Summit on Malaria and NTDs,

alongside the 26th Commonwealth

Heads of Government meeting. The

Kigali Declaration will put country

ownership of NTD programmes,

integration and cross-sectoral

collaboration at the front and centre

to ensure that these programmes are

sustainable in the long term.

The Declaration provides the

opportunity to mobilise the political

will, community commitment,

resources and action needed to end

unnecessary suffering from NTDs.

Signatories of this declaration

pledge to do their part to ensure that

NTDs are eradicated, eliminated or

controlled by 2030.

Commitment to ending NTDs is needed

By working together, adopting peoplecentred

approaches and working

across sectors in an integrated manner,

we can end NTDs and achieve WHO

2030 NTD road map targets. Now

is the moment for leaders, donors,

companies and organisations to

make endorsements behind the

Kigali Declaration and show they are

100% committed to ending NTDs.

These commitments will help relieve

needless suffering, decrease the

health-related drivers of poverty, make

our health systems more resilient and

our world an equitable and safer place.

For more information visit 100percentcommitted.com

WRITTEN BY

Thoko Elphick-Pooley

Executive Director,

Uniting to Combat

Neglected Tropical

Diseases

Ending malaria and NTDs will save lives, advance equity and build resilience.

Over the past two years, no

country has been spared

the impacts of COVID-19, a

deadly infectious disease that

killed millions, infected millions and

devastated communities, economies

and health systems. The same impacts

can be attributed to malaria and

neglected tropical diseases (NTDs)

however, these diseases have been

around for millennia and typically

prey on the world’s poorest in Africa.

Ending preventable and treatable diseases

In 2000, global leaders committed

funding and action to reduce cases

and deaths caused by these diseases.

Thanks to this strong political will

and increased funding, by 2015

malaria deaths were cut by over

half and more than 5 billion NTD

preventive treatments were delivered.

The tremendous progress achieved

through global collaboration and

commitment prompted more

ambition to end these preventable

and treatable diseases by 2030.

In the case of malaria, a turning

point was the launch of the Global

Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis

and Malaria. Significantly, 20 years

later, the Global Fund, working with

the US President’s Malaria Initiative

and country partners, has saved 44

million lives.

But in the last two years, progress

has slowed and cases and deaths are

on the rise. With challenges of drug

and insecticide resistance, COVID-19

and humanitarian emergencies, the

world is at a precarious juncture in the

fight against malaria.

Better prepared for better results

However, there is hope on the horizon.

Thanks to greater country ownership,

better use of data and targeting of

existing and new tools, a pipeline

of transformative tools and strong

political will. And, if governments,

the private sector, communities and

partners come together later this year

to fulfil the Global Fund’s Seventh

Replenishment goal of at least USD 18

billion, we can turbocharge progress

again toward a malaria-free future.

By mobilising new funding, we can

scale up existing and breakthrough

tools, including new nets and vaccines

and better target interventions to the

local context. We also must invest

more in research and development to

deliver transformative new tools, such

as second-generation vaccines, that

will accelerate our path to malaria

eradication.

Critically, these innovative

approaches will also help countries

strengthen their health systems,

allowing them to better protect citizens

against malaria and NTDs and be

better prepared for future pandemics.

With COVID, we’ve seen what the

world can do when it comes together.

Let’s recommit to saving millions more

lives from malaria and NTDs, invest

in health and deliver a more equitable

world for all.

WRITTEN BY

Dr Corine Karema

Interim CEO, RBM

Partnership to End

Malaria

Read more at

campaign.co.uk

@GlobalcauseUK @MediaplanetUK

Contact information: uk.info@mediaplanet.com or +44 (0) 203 642 0737

Please recycle

Industry Manager: Benedetta Marchesi benedetta.marchesi@mediaplanet.com Campaign Assistant: Mia Huelsbeck Managing Director: Alex Williams Head of Strategic Partnerships: Roz Boldy |

Head of Production: Kirsty Elliott Senior Designer: Thomas Kent Design & Content Assistant: Aimee Rayment | Digital Manager: Harvey O’Donnell Paid Media Strategist: Jonni Asfaha Social & Web Editor:

Henry Phillips Digital Assistant: Carolina Galbraith Duarte | All images supplied by Gettyimages, unless otherwise specified

02 MEDIAPLANET

READ MORE AT GLOBALCAUSE.CO.UK

A PROMOTIONAL SUPPLEMENT DISTRIBUTED ON BEHALF OF MEDIAPLANET, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTENTS

Image provided by The Carter Center

This is how we finish off Guinea worm

In the past 200 years, humankind has made incredible progress against many threats to health: vaccines, medicines and other innovations

have saved millions of lives from feared killers, from malaria to cancer. But only one human disease – smallpox – has ever been eradicated.

WRITTEN BY

Dr Tedros Adhanom

Ghebreyesus

Director-General, World

Health Organization

WRITTEN BY

Jason Carter

Chair, Board of Trustees,

The Carter Center

Find out more at

cartercenter.org

A

massive campaign has now driven polio to the

brink of eradication, but less noticed by the rest of

the world, we stand on the threshold of consigning

another disease to the history books: Guinea worm.

While Guinea worm is largely unknown to people in highincome

countries, it has afflicted people in Africa, Asia and

the Middle East for millennia.

Last year there were just 15 reported cases of Guinea worm

disease, compared with an estimated 3.5 million in 1986,

when The Carter Center and the World Health Organization

launched the Guinea Worm Eradication Program. Since

then, our two organisations have worked closely with

governments, the US Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, and partners including the United Arab

Emirates, which hosted the Guinea Worm Summit

in Abu Dhabi in late March.

The official name of Guinea worm is Dracunculus

medinensis, which derives from the Latin for “little dragon,”

and for good reason. People contract the disease by drinking

untreated water that contains tiny fleas that harbour larvae,

which grow in the intestine into worms up to one metre long.

About a year later, they emerge through painful blisters on

the skin. Those infected can’t work or go to school while a

worm is emerging. Extracting a worm from the body can take

a week or longer and is an excruciating process.

There is no vaccine to prevent infection and no medicine

to treat it. But what pharmaceuticals couldn’t do, the

Guinea Worm Eradication Program has accomplished with

humble water filters, a basic larvicide, and the partnership

of millions of people, in some of the world’s poorest

countries, who made simple changes in their behaviour.

Of course, simple doesn’t mean effortless or troublefree.

Progress has been bumpy, complicated by poverty,

the remoteness of affected communities, storms, floods,

droughts, conflict, and, most recently, a pandemic. In 1995,

former US President Jimmy Carter had to negotiate a cease

fire to enable health workers safe passage in the midst of

Sudan’s civil war. Through all this, the communities in

which we work have taken ownership and continued their

unceasing efforts.

Today, Guinea worm disease remains endemic in just five

countries: Angola, Chad, Ethiopia, Mali and South Sudan.

Two other countries – the Democratic Republic of the

Congo and Sudan – are on the path to being certified free of

the disease. Although Cameroon is certified, it is addressing

recent cross-border infections.

At the Summit in the UAE, we joined Ministry of Health

representatives to discuss the Abu Dhabi Declaration on the

Eradication of Guinea Worm Disease.

The declaration reaffirms that the governments of

the endemic countries and we, their partners, will

work urgently for eradication by 2030. It calls for active

leadership nationally and locally, sufficient budget support,

robust implementation of interventions, transparent

communication, rapid provision of safe water everywhere

and safety for health workers.

Preventing the spread of Guinea worm from one

country to another is also critical to accelerate the global

interruption of transmission and requires strengthening

cross-border surveillance and collaboration. Several

countries have made commendable efforts in this direction,

with support from WHO.

We applaud the leaders of the countries who made these

commitments, but they can’t do it alone. Now other global

leaders need to marshal the sustained funding to finish the

job. The last mile of disease eradication is complex, and

momentum can wane as the numbers get close to zero,

especially as other urgent health crises emerge. But if we fall

short of eradication, the disease could return to its former

levels, which would bring needless suffering and economic

challenges to poor communities.

We stand tantalisingly close to a monumental victory for

public health – and for humanity. The eradication of Guinea

worm will be the fulfilment of President Carter’s vision and

the culmination of decades of difficult and often dangerous

work in partnership with some of the poorest, most isolated,

most marginalised people on Earth.

The real heroes in the Guinea worm story are the

thousands of volunteers in more than 23,000 villages who

do the hard work in their own communities. Defeating this

scourge is a triumph of persistence and people, more than

technology and medicine. Village by village, across sub-

Saharan Africa and parts of Asia, citizens have mobilised

and organised to safely treat water sources, distribute

filters, and spread the word on how to change behaviours to

protect themselves and their children.

The victory will be theirs when, sometime before the end

of the decade, 15 cases become zero. To get there, all of us

must do our part to travel the last mile in eradication and

move toward a world free of Guinea worm and the terrible

suffering it brings.

Paid for by

The Carter Center

READ MORE AT GLOBALCAUSE.CO.UK MEDIAPLANET 03

A PROMOTIONAL SUPPLEMENT DISTRIBUTED ON BEHALF OF MEDIAPLANET, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTENTS

Tackling malaria and

NTDs contributes to more

resilient health systems

People living in fragile settings are the most at risk

of contracting malaria and NTDs yet they are the

least likely to have access to adequate health care.

Building the capacity of local health

facilities and community health

workers to prevent, diagnose and treat

malaria and NTDs in fragile settings

can lead to more resilient health systems and

greater global health security overall.

According to Dr Lali Chania, Tanzania

Country Director of IMA World Health:

“Health systems in fragile settings, if

they exist at all, are beset by external and

internal challenges, including but not

limited to violence, lack of infrastructure

and resources, corruption, access inequities,

weak governance and limited human capital.

Yet fragile settings have a higher disease

burden than other low-income countries.”

Poor public health perpetuates the cycles

of poverty and fragility and vice versa.

As the number of fragile settings increases,

so too does global insecurity and economic

instability. That is why IMA World Health

is committed to health systems

strengthening in fragile settings.

Building on malaria and NTD programming

successes

“The local partnerships, trust and capacities

we have built through our malaria and NTD

programming in fragile settings are key for

any health systems strengthening efforts

to be successful in these complex

environments,” says Chania.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo

and South Sudan, the organisation has

collaborated with local health facilities

to improve access to malaria prevention,

diagnostic and treatment services for more

than 11.4 million people.

Across Tanzania and Haiti, 28.8 million

people are no longer at risk for lymphatic

filariasis since IMA has strengthened the

capacity of local health systems to sustainably

administer NTD control measures. IMA’s

health partners in these fragile settings are

leveraging these capacities to meet other

critical health care needs.

Dr Chania suggests: “The surveillance

and case-based notification and response

capacities required to eliminate malaria

and NTDs are also what is required to stop

epidemics from becoming pandemics, like

COVID-19. Integrating those capacities into

health systems will not only improve that

system’s resilience to the shocks common

in fragile settings, it will improve global

health security.”

Paid for by IMA World Health

Find out more at

imaworldhealth.org

WRITTEN BY

Dr Lali Chania

Director, IMA

Tanzania Country

Investing in

ending malaria

and NTDs for

a safer world

A world free of malaria and NTDs is

possible. Investing now to end these

diseases will save millions of lives and

protect against future pandemics.

This year, the global community has two

historic opportunities to recommit to

ending malaria and neglected tropical

diseases (NTDs)—by mobilising at least USD

18 billion to replenish the Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

Tuberculosis and Malaria and by supporting the

Kigali Declaration on NTDs to deliver the targets set

in the World Health Organization’s NTD Roadmap

(2021-2030).

Supporting national malaria and NTD programs

Enormous strides have been made against these

diseases since 2000. Global Fund investments helped

scale up lifesaving interventions, contributing

to over 10 million deaths averted from malaria.

The 2012 London Declaration on NTDs, signed by

governments, pharmaceutical companies, endemic

countries, global health organisations, and the Bill &

Melinda Gates Foundation, nearly doubled medicine

donations by the pharmaceutical industry—reaching

over a billion people a year from 2017 to 2019.

Yet these diseases continue to take lives and put

billions of people at risk— and COVID-19 further

hinders progress.

We can end malaria and NTDs and keep us safer

from future health threats. By supporting national

malaria and NTD programs that drive progress

against these diseases, boosting investments, and

better integrating these programs into national

health systems millions of lives can be improved

and saved.

Community-based disease monitoring and tracking

With the goal of ending malaria and NTDs, the Gates

Foundation co-invests and partners with national

programs, pharmaceutical companies, product

development partnerships, research institutes

and global and local NGOs. A primary focus is on

increasing the use of digitised data systems for realtime

disease monitoring to better target delivery of

interventions.

For example, Initiatives like Visualize No More

Malaria and the Lymphatic Filariasis Campaign

Digitization in India are generating valuable insights

at the community level that support decision-makers

to transform healthcare delivery.

Community health workers are at the heart of

national malaria and NTD programs, providing

essential services for millions of people—often in

remote regions. The trust built with the communities

they serve provides a foundation for digitised disease

©Speak Up Africa

monitoring and adaptation of services to emerging

health needs, like COVID-19, showcasing how investments

in malaria and NTDs can help prevent future

pandemics.

Increased financial and political commitments

We are already seeing examples of commitments

and approaches that are helping malaria and NTD

programs to drive lasting progress.

Twenty five sub-Saharan African countries

have launched local Zero Malaria Starts with Me

campaigns and End Malaria Councils to mobilise

country resources and action. The African Union

and Uniting to Combat NTDs recently signed an

agreement to end NTDs by 2030. We are also seeing

critical accountability mechanisms emerge with the

integration of NTDs into national health strategies

and the African Leaders Malaria Alliance scorecard.

To support this stepped-up leadership, global

leaders must join in solidarity and increase funding

to deliver a safer, more equitable world free of malaria

and NTDs.

WRITTEN BY

Katey Einterz Owen

Director, Neglected

Tropical Diseases,

Bill & Melinda Gates

Foundation

WRITTEN BY

Philip Welkhoff

Director, Malaria,

Bill & Melinda Gates

Foundation

©Speak Up Africa

Community health workers are at the

heart of national malaria and NTD

programs, providing essential services

for millions of people.

04 MEDIAPLANET

READ MORE AT GLOBALCAUSE.CO.UK

A PROMOTIONAL SUPPLEMENT DISTRIBUTED ON BEHALF OF MEDIAPLANET, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTENTS

Institute will shine its light on disease elimination at summit

The forthcoming Kigali Summit provides an opportunity for knowledge to be shared to help combat malaria and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

INTERVIEW WITH

Simon Bland

CEO, Global Institute

for Disease Elimination

(GLIDE)

WRITTEN BY

Sheree Hanna

Paid for by

Global Institute for

Disease Elimination

Launched at the end of 2019, the Global Institute

for Disease Elimination (GLIDE), a non-profit

organisation based in Abu Dhabi, is committed to

helping its partners go further and faster towards the

elimination and ultimate eradication of infectious diseases,

with a current focus on malaria, polio, lymphatic filariasis

and onchocerciasis.

The Institute was jointly founded by His Highness Sheikh

Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the Crown Prince of Abu

Dhabi, and the Bill and Melinda Gates

Foundation, and builds upon a longstanding

history of investment in global

health.

GLIDE’s CEO, Simon Bland, says: “The

Kigali Summit comes at a time where

some of the world is seemingly emerging

from COVID-19, so understanding its

impacts and lessons will be vitally

important as we look ahead.

“We need more money for health,

but also more health for the money.

We need efficiencies, synergies, effective coordination and

cooperation and synchronicity of services provision across

diseases. We want to help break down barriers and silos.”

Finding the best outcome

Bland says a successful Summit for GLIDE would result

in high-level political commitment from across the

Commonwealth for disease elimination, with increased

commitments to tackling neglected tropical diseases (NTDs),

We need efficiencies, synergies,

effective coordination and

cooperation and synchronicity of

services provision across diseases.

and momentum for a successful Global Fund replenishment

in September.

The Summit will be held alongside the 26th

Commonwealth Heads of Government (CHOGM) meeting in

Rwanda in June.

The rationale behind eliminating or eradicating infectious

diseases means no longer having to invest or survey them,

thereby freeing up money and resources for other priorities.

Bland says: “Calling to end disease is a bold statement of

ambition which can excite, motivate

and attract strong political will for

such an audacious goal. However,

there is a caveat: it is easier to call for

elimination than to deliver it, and the

last mile of elimination is the hardest.”

Innovation is main objective

Innovation is a key objective for the

Institute, which looks to foster and

scale innovation not only for new

tools and technologies, but also for

new strategies for health systems strengthening. GLIDE

is working with partners to convene community, country

and global experts to explore the rationale for programme

integration, keeping in mind that efforts should result in

improved outcomes for all health programmes involved.

The Kigali Summit is an opportunity not only for

galvanising political commitment, but also for stakeholders

from the malaria and NTD communities to identify potential

opportunities for joint advocacy, programming and finance.

Find out more at

glideae.org

Taking a multisectoral

approach in the fight

against malaria

Malaria does not exist in isolation and will require a cross-sector

response through coordination, policy and funding at global and

national level to ensure a malaria-free future for all.

INTERVIEW WITH

Joseph Lewinski

Multisectoral Malaria

Project Lead, Catholic

Relief Services

WRITTEN BY

Meredith Jones

Russell

This cross-sector response

to malaria is called

multisectoral programming.

It uses different sectors to

help bridge funding gaps in malaria

programming, increasing access

and use of malaria services in

communities that are often missed.

Joseph Lewinski, Multisectoral

Malaria Project Lead at Catholic

Relief Services (CRS), explains: “I

don’t think we have seen a country

that has eliminated malaria without a

multisectoral approach.”

Sectors driving the biggest impact

include agriculture, education,

humanitarian response, urban

development, extractive industries,

population movement and defence.

CRS is investing in multisectoral

programming to help ensure these

critical connections are made,

especially in countries with the highest

number of malaria cases.

Image provided by

Catholic Relief Services

“This concept, which has existed

since the first malaria elimination

efforts, proports that by including

other sectors in programming, we can

address common causes that help

spread malaria in endemic countries

and develop malaria ‘smart’ policy to

mitigate their effect,” Lewinski says.

Dual impact approach

Multisectoral approaches have a

positive impact on both malaria

prevalence and on the other sectors

involved.

“By working with the education

sector, you get more consistent access

to children, who are more likely to

be impacted by malaria,” Lewinski

explains. “You can train teachers to

identify signs and symptoms and

strengthen referral system so kids can

get diagnosed and treated quicker.”

“In rice farming agriculture,

increased production can impact

mosquito breeding and, thus, malaria

transmission. A multisectoral

approach can provide dual impact,

in this case, ensuring productive

agriculture production and also in

reducing malaria prevalence. Globally,

malaria stakeholders need to adopt

proactive policy. National malaria

control programmes are needed.

On a community level, farmers and

communities must be considered in

the decision-making process.”

Working towards elimination

In some circumstances, multisectoral

programming can help countries

eliminate malaria completely.

“Multisectoral programs have

historically been used to help reach the

last few cases within countries close

to elimination,” Lewinski explains.

“In the Mekong sub-region, we see that

by working with extractive industries

we can ensure we know where forest

working populations are and find those

last cases.”

But Lewinski emphasises

multisectoral approaches can benefit

all countries with malaria cases.

“This isn’t just an approach for

countries eliminating malaria. By

setting up these systems in high

burden countries, we can ensure this

holistic, integrated response, which

is vital for meeting malaria control

and elimination goal. It just requires

upfront investment, and bringing

together stakeholders who wouldn’t

normally work together, to create

practical and novel solutions.”

Paid for by

Catholic Relief

Services

Scan the QR code

to find out more

READ MORE AT GLOBALCAUSE.CO.UK MEDIAPLANET 05

A PROMOTIONAL SUPPLEMENT DISTRIBUTED ON BEHALF OF MEDIAPLANET, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTENTS

The health of women

and children is threatened

by a treatable disease

Pregnant women, teenage girls and children remain

disproportionately vulnerable to malaria.

Malaria is one of the world’s

oldest, deadliest diseases,

stealing young futures and

claiming the life of a child

every minute, despite being treatable,

preventable and beatable.

The heavy human cost of malaria

can be measured in the number of

each and every life lost and the many

more that are diminished, with the

latest World Malaria Report revealing

241 million cases and 627,000 deaths

worldwide in 2020 - the highest

number of deaths in nearly a decade.

Malaria deaths are increasing

Tragically, millions of pregnant

women, adolescent girls and young

children remain disproportionately

vulnerable to malaria, with the

disease cited as the third highest

cause of death in teenage girls aged

15-19 in sub-Saharan Africa in 2019.

Despite substantial efforts to

continue malaria services during

COVID-19, disruptions resulted in

an additional 47,000 malaria deaths

in 2020 and, with the impacts of

the pandemic ongoing, so too are

disruptions to healthcare. The

pandemic has also weakened

economies and exacerbated alreadyfragile

health systems which paints an

even darker picture for the health of

women and children going forward.

Limited access to preventable treatment

In 2020, a staggering 11.6 million

pregnant women contracted malaria

across sub-Saharan Africa, and more

than two-thirds of eligible women

across 33 African countries did not

receive the full course of preventive

malaria treatment (IPTp-SP)

recommended by the World Health

Organization.

Malaria in pregnancy has been

associated with maternal anaemia,

exposing the mother to an increased

risk of death before, during and after

childbirth. The dangers are also

substantial for the newborn child,

including low birth weight which

can impact growth and cognitive

development.

Achieving key global malaria targets

One third of the Global Fund to Fight

AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria’s

investment goes towards building

inclusive health systems, ensuring

that women and girls have access to

quality health services for malaria

and sexual and reproductive health.

This helps boost progress toward key

global malaria targets and supports

many of the Sustainable Development

Goals including fighting poverty,

improving gender equality and

universal health.

The Global Fund’s seventh

replenishment target this Autumn is

to raise at least USD 18 billion to fight

the three diseases, which would save

20 million lives, cut the malaria death

rate by 64% and build a healthier,

more equitable world, making the

UK’s financial commitment to ending

malaria more critical than ever.

Malaria is a disease that this

generation can end, but only

if we act now.

WRITTEN BY

James Whiting

CEO, Malaria No More UK

Genuine intersectoral

collaboration needed to

achieve better progress

against vector-borne NTDs

WRITTEN BY

Ashok Moloo

Information Officer,

WHO Department of

Control of Neglected

Tropical Diseases

WRITTEN BY

Dr Raman Velayudhan

Head, Veterinary Public

Health, Vector Control

and Environment,

WHO Department of

Control of Neglected

Tropical Diseases

This article was

originally published

on the World Health

Organization’s

website. Scan the

QR code to access

the original article

The world needs to work better and collaborate with

sectors beyond health to implement the Global Vector

Control Response 2017–2030 (GVCR).

The silent spread of vectors over the years means

more countries are now exposed to arboviral

diseases, with human activities facilitating their

survival and propagation.

“It is time that vector control programmes work jointly with

city planners, environmentalists, engineers and sectors that

manage water and sanitation,” says a leading expert during a

WHO-hosted webinar on ‘Reducing the burden and threat of

vector-borne diseases to achieve the NTD road map targets.’

“We face the prospect of seven out of 10 people living in cities

and urban areas globally by 2050.”

Focussing on prevention

“One of the things which is critical as we build out future

cities … we really need to do better in the area of prevention

… reducing the habitats of all mosquito species,” says

Steve Lindsay, panellist and former Professor at Durham

University, United Kingdom.

This implies reducing the breeding sites for Aedes

mosquitoes that transmit vector-borne diseases such as

dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever and Zika. This can be

done by enhancing access to piped water, constructing

houses with built-in screens to block mosquito entry,

clearing waste, improving drainage and keeping the

environment clean.

More than half the world’s population is at risk of

infection from vector-borne diseases.

Challenges to meet targets

While the GVCR is on track for some activities, amounting to

an almost 10% reduction in global mortality over the past five

years, for many other activities targets have not been reached.

A progress report outlining achievements and challenges

will be submitted to the 75th World Health Assembly in

May 2022.

Assessing global risk

More than half the world’s population is at risk of

infection from vector-borne diseases, especially dengue,

leishmaniasis and malaria.

Vectors are responsible for transmitting many neglected

tropical diseases, mostly among the poorest populations

where there is a lack of access to adequate housing, safe

drinking-water and sanitation.

During the past two decades, many vector-borne diseases

have emerged or re-emerged, spreading to new parts of the

world. Dengue alone has increased six-fold since 2000 and

it affects over 130 countries and still there are no effective

drugs, vaccines and sustainable vector control tools, making

it more neglected.

Other factors, such as environmental changes, increased

international travel and trade, changes in agricultural

practices and rapid, unplanned urbanisation have

facilitated the spread of many vectors worldwide.

Current efforts to address the needs for better diagnostics,

vaccines and sustainable innovative vector control

interventions such as the use of Wolbachia, spatial repellents

etc are encouraging new hope in the horizon to address the

void and meet the goals set in the NTD roadmap 2021-2030.

06 MEDIAPLANET

READ MORE AT GLOBALCAUSE.CO.UK

A PROMOTIONAL SUPPLEMENT DISTRIBUTED ON BEHALF OF MEDIAPLANET, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTENTS

We need to be more adaptable to

control the resurgence of malaria

spatially contextualised information.

This can be delivered via different

innovative systems.

For example, in Equatorial Guinea,

MCD is using a tablet application

(CIMS) to collect and use field-level

malaria control data at the household

and individual levels. Meanwhile, in

other countries, MCD is supporting the

integration of major health information

databases to a common platform.

“Having a more efficient way of

entering, processing and analysing

data is a big benefit in the fight against

malaria,” says Julie Niemczura, Senior

Program Manager at MCD. “Real-time

access to information shortens the

feedback loop so that any deficiencies

can be corrected immediately.”

INTERVIEW WITH

Guillermo García

Senior Program

Manager, Bioko Island

Malaria Elimination

Project, Medical Care

Development

In recent years, malaria cases have been on the rise. The disease

transmission has changed — so the response to it must change

too with a new, adaptive approach based on evidence and data.

Image provided by MCDI

An adaptive approach isn’t

simply beneficial for controlling

malaria. It can also promote

sustainable health systems,

strengthening their ability to

respond rapidly and effectively

to unforeseen challenges.

INTERVIEW WITH

Olivier Tresor Donfack

Technical Coordinator,

Bioko Island Malaria

Elimination Project, Medical

Care Development

Paid for by Medical

Care Development

International

Controlling malaria

is — and has always

been — a mammoth

challenge. Decades

after the first Global

Malaria Eradication

Programme was

launched in 1955, this

life-threatening disease still brings

untold misery and death to many parts

of the world. Indeed, malaria cases are

on the increase. According to figures

from the World Health Organization,

there were 241 million cases in 2020

compared to 227 million in 2019.

There are a number of reasons

for this rise, says Guillermo García,

Senior Program Manager, Bioko Island

Malaria Elimination Project at MCD,

a global public health non-profit

providing interventions across several

health areas. “There are challenges,

for example drug and insecticide

resistance,” he says.

Understanding why there

is a resurgence in malaria

Climate variability may also be partly

responsible for the resurgence, as

warmer temperatures and increased

rainfall make better breeding

conditions for mosquitoes; plus, the

behaviour of mosquitoes is changing.

“In some areas, there is evidence

that insects are biting earlier in the

evening, before people are indoors

or protected by bed nets,” says

Olivier Tresor Donfack, Technical

Coordinator, Bioko Island Malaria

Elimination Project, MCD.

To make matters worse, malaria

control has faced huge funding

constraints — and increased

competition due to the global

pandemic. This has hit resource-poor

communities particularly hard as

they face a disproportionate burden of

illness, death, and declining economic

productivity, welfare and wellbeing.

Benefits of an adaptive

evidence-based approach

To effectively respond to the

resurgence and ultimately achieve

elimination, it’s imperative that

funding for malaria control continues.

“Of course, any tools that are proven

to work should continue to be

deployed,” says García. “But in this

fight, there is often a need for more

innovation and adaptation.” After all,

when traditional methods of malaria

control prove inadequate, new

approaches must be found.

This is why it’s important to adapt

and optimise malaria control strategies

through evidence-based decision

making, based on the use of real-time

Building local capacity with

training and support

Not all solutions have to be hi-tech.

“In some health facilities, wall charts

filled out by hand are a simple way to

track trends,” says Niemczura. “But

how ever health managers receive

the information, it’s crucial that they

know how to use the systems and

interpret the data to affect positive

outcomes.” This requires building

local capacity with robust training

and support, delivered via different

institutional partners.

An adaptive approach isn’t simply

beneficial for controlling malaria. It

can also promote sustainable health

systems, strengthening their ability

to respond rapidly and effectively to

unforeseen challenges and emerging

threats, such as the COVID-19

pandemic. “In Equatorial Guinea, a

team that was fully trained to deliver

clinical trials for malaria was quickly

able to adapt to meet the demands of

COVID-19,” remembers García.

Yet despite the increase in malaria

cases, it’s important to keep things

in perspective. “The resurgence does

not mean that control programmes

are failing,” stresses Donfack. “In

fact, we’re optimistic that trends

will change — if programmes adopt

adaptive control measures based on

evidence and data.”

INTERVIEW WITH

Julie Niemczura

Senior Program

Manager, Medical Care

Development

WRITTEN BY

Tony Greenway

Find out more at

mcd.org

READ MORE AT GLOBALCAUSE.CO.UK MEDIAPLANET 07

A PROMOTIONAL SUPPLEMENT DISTRIBUTED ON BEHALF OF MEDIAPLANET, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ITS CONTENTS

Invest in

malaria and

NTDs to fight

future disease

outbreaks

On World Malaria Day, and ahead of the malaria & NTD summit in

Kigali, Rwanda, it is important we recognise the role of strengthening

health systems to prepare for the next global disease outbreak.

©James Roh/Cotopaxi Foundation

WRITTEN BY

Andrea Lucard

Executive Vice

President of Corporate

Affairs, Medicines for

Malaria Venture

WRITTEN BY

Michelle Childs

Head of Policy

Advocacy, Drugs for

Neglected Diseases

initiative

Paid for by Medicines for

Malaria Venutre (MMV)

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the term

“global health” was often used with

reference to low and middle-income

countries. If the past two years have taught

us anything, it is that we are all “global

health”—North or South, rich or poor, microbes and

particles connect us all.

This World Malaria Day is the perfect time to

recognise that investments in combatting diseases

that often occur amongst the poorest populations

allow countries to build more resilient health

systems. These systems can be deployed in response

to the next global health emergency.

Unlocking innovation

Outbreaks are more likely to occur where health

systems are fragile, and treatment and prevention

tools are scarce. When financial incentives for health

research are low or non-existent, such as in the

context where malaria and neglected tropical diseases

(NTDs) prosper, product development partnerships

(PDPs) are a proven path to unlocking innovation.

The PDP model leverages partners from the public

and private sectors to innovate health tools where a

single entity would be unable or unwilling to take on

the investment.

Since their establishment around 20 years ago, a

small community of 12 PDPs have delivered more

than 65 new health technologies that have protected

and saved the lives of more than 2.4 billion people.

Highlights from two of these PDPs include the

first new single-dose treatment to prevent malaria

relapse in over 60 years, developed in partnership

by Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) and GSK;

and the first all-oral treatment for sleeping sickness,

developed by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases

initiative (DNDi), Sanofi and the National Sleeping

Sickness Control Programme in the Democratic

Republic of Congo.

Preparing to combat future outbreaks

From the laboratory to the patient, PDPs have

engaged the populations they serve, helping to

expand local expertise and strengthen healthcare

systems. These capabilities can be called upon to fight

disease outbreaks when new health crises emerge.

In Africa, PDPs have helped strengthen local

capacity to research the world’s most neglected, often

deadly, diseases, such as visceral leishmaniasis and

sleeping sickness. DNDi has supported the training

of laboratory technicians, nurses and physicians

to conduct state-of-the-art clinical research for the

treatment of NTDs. In 2020, these trained resources

were quickly mobilised to launch the ANTICOV clinical

trial – a large trial to find treatments for mild-tomoderate

cases of COVID-19 in low-resource settings.

In addition to supporting local research

capability, PDPs are also working to build on

existing manufacturing capacity for medicines

closer to where they are most needed. With only

around 375 pharmaceutical manufacturers, Africa’s

public sector relies disproportionately on imported

medicines for malaria and NTDs – COVID-19

highlighted this vulnerability.

With funding from Unitaid, MMV is supporting

a Kenyan pharmaceutical manufacturer, Universal

Corporation Ltd, and two Nigerian manufacturers,

Emzor and Swipha, in the development of WHOprequalified

preventive medicines for malaria in

pregnancy. This increased self-sufficiency within the

continent will potentially provide not only adequate

supplies of these life-saving medicines, but also

quality-assured medicines for other diseases.

Like other tropical diseases, malaria thrives where

access to basic health services is limited. Common

symptoms, such as fever, have been shown to mask

indications of other infections, including COVID-19.

This burdens health systems and allows for disease

to spread undetected across borders. Through a

project supported by MMV, Transaid (UK) and

Zambia’s National Malaria Control Programme, local

community members — be they fisherman, farmers,

or primary school teachers — use training systems

established for malaria to inform fellow community

members about COVID-19 related policies, such as

handwashing and social distancing.

PDPs invest where others do not and this is

crucial to strengthening global health security.

The next health emergency is likely just around

the corner. In preparation for this inevitability,

sustained and flexible support to the invaluable

work of PDPs is needed.

Find out more at

mmv.org

08 MEDIAPLANET

READ MORE AT GLOBALCAUSE.CO.UK